This is the only photo I have of my Grandad, John Dodd Vause. The blurred image of him and my Dad must have been taken some time before 1953, because that's the year he died, seven years before I was born. Just like in most families, there were stories about him that I didn't question as I grew up. Years later, now that I write fiction, I decided to research my family tree to see if there were any stories, people or events I could use for inspiration. Finding out about my Grandad's time as a soldier turned out to be an interesting and insightful journey along the road of truth and myth.

The Family Story

My Dad always said that my Grandad refused to talk about his WW1 experiences. The only comment he ever made was that 'if he died and went to Hell it would be like Passchendaele.' The story in the family was that my Grandad had been one of the 'Boy Soldiers' and had run away, under age, to volunteer for the army. Another part of that story was that he'd travelled from his native Northumberland to join the Lancashire Fusiliers, thereby 'tipping his hat' to his own father's roots and also avoiding telling his mother that he'd joined up. Over the years, I never questionned these stories or actually thought that much about them. They were just there and I accepted them, but as I got older, like so many people, I became interested in finding out more.

Finding Out the Facts

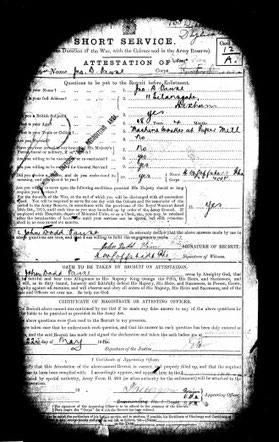

After searching online and also communicating with the Fusiliers Museum at Bury, Lancashire, I discovered that the family stories were completely untrue. Above is my Grandad's enlistment paper. He was a private in the Lancashire Fusiliers, as we thought, but didn't run away, under age, to volunteer. He turned eighteen in January 1916. Unfortunately, conscription was introduced two months later in March, and my Grandad was called up in May. The records at the Fusiliers Museum show that he was meant to be enlisted into the Royal Field Artillery (RFA) by September 1916, but was posted instead to the Fusiliers, because the infantry units were short of men. Consequently, the enlisting decision and posting placement were decided for my Grandad. He had no say in the matter.

I wanted to find out about the comment my Grandad made about Passchendaele and I contacted the Passchendaele 1917 Memorial Museum, near Ypres, in Belgium. They were able to tell me that my Grandad was a private in the 15th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers, and that this battalion never took part in the Battle of Passchendaele. They were involved further west, in the coastal defences in the Koksijde and Nieuwpoort areas.

A hundred years later, I felt a mixture of emotions at the news that my Grandad was not at Passchendaele after all; relief for him, but sadness for the thousands of soldiers who were there. This was the infamous, terrible battle in which the mud was just as much a killer as the enemy. To be on coastal defences somehow sounded much safer, less serious than the battle raging nearby.

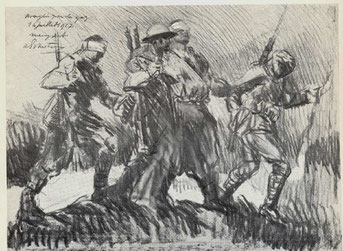

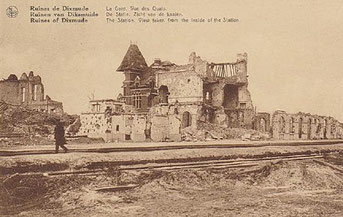

How wrong I was. The drawing on the left was sketched by a soldier at the coastal defences and shows a group of soldiers, gassed and blind, being led to safety. The coastal defences were no easy posting, and no respite from the campaign around Ypres. The coastal areas around Nieuwpoort and Diksmuide were also the scene of fierce fighting and heavy bombardment. The photo below shows the trench known as the 'Trench of Death'.

Did Experience Cause an Emotional Change?

In 1918 my Grandad was twenty years old and had been in active service for almost two years. There is sketchy information in the records that in 1918 he was wounded and spent time in a military hospital back in England. He received a gun shot wound and also a bayonet wound, evidence of difficult hand to hand fighting. He was also gassed, according to my Dad, but the army never kept records of gas victims.

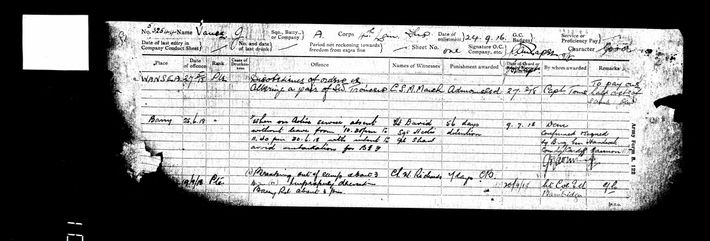

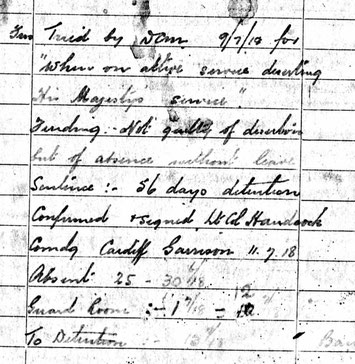

It's at this point that things seemed to have changed for my Grandad, and if I could ask him, I think he changed too. The above image is his discipline sheet. The second entry is particularly important. The entry, dated 25th June, states that 'when on active service absent without leave from 10.40 pm to 11.40 pm 30.6.18 with intent to avoid embarkation for BEF' (the British Expeditionary Force). The discipline sheet shows my Grandad was sentenced to 56 days in military prison. Basically, he went missing to avoid going back to the front.

I found a second reference to this event in a different document. It was emotional to read the words 'Finding: Not guilty of desertion but of absence without leave', because in WW1, the British army executed deserters. Many of them were very young and a hundred years later, we understand that many of them probably suffered from PTSD. The Fusiliers Museum staff explained that the military court probably decided on 'absent without leave' because my Grandad was still in the UK when he went missing, and not at the front, but what a relief that this decision was made, or our subsequent family story would have changed. If my Grandad had been found guilty of desertion and shot, some of us would not even exist.

The third entry on my Grandad's discipline sheet shows he broke out of camp at three o'clock in the morning on 19th September 1918 and was confined to barracks for seven days. Two months later the war ended.

Final Thoughts

What do we learn when we look at war? Current events in Ukraine suggest we learn nothing. And how do I feel after I found out the details of my Grandad's WW1 story? I feel I know him a little better. I also sympathise with his 1918 experience. I think he changed at the moment when he was wounded and he couldn't face going back to the front line. Speaking as a writer, his story has inspired some future writing plans and grounded me in the world of WW1 a bit more, but more importantly, I've gone over and over an obvious question: Was my Grandad a coward? Personally I don't think so, and what right do any of us have to judge?

Write a comment

Christine (Wednesday, 27 July 2022 12:02)

Powerful story, Maggie, and absolutely true: we have no right to judge.

Amancio (Wednesday, 27 July 2022 14:34)

So often the popular histories we learn are not true. So much of our own identities and life decisions can be effected by those false narratives. I am interested to learn how and why such false stories, either romanticized or embellished, come to be. Do you have a clue as to where the untruths in your grandfathers story started, and why? Perhaps simply from his own silence on the topic?

Maggie Holman (Thursday, 28 July 2022 06:33)

I agree, Amancio. I'm not sure where our family stories are from. Perhaps my Grandad made the Passchendaele comment to prevent people asking him further questions, and then people filled his silence with their own assumptions. Unfortunately, I'll never know.

Phil Thredder (Friday, 05 August 2022 20:38)

Good,honest writing,well put together

Maggie Holman (Saturday, 06 August 2022 06:06)

Thank you.

Alan McThredder (Tuesday, 23 August 2022 19:37)

Hi Maggie,

We all have a desire to make the memories of our ancestors inspiring. Often wars treats people like bits of garbage and nobody wants to believe fate threw them into the bin like trash. So, we tell stories that glorify, or at least humanise their experiences. We tell families that they died quickly and without pain; we tell them they died doing something brave and necessary - anything but say they were just one of a thousand machine-gunned that week for no gain at all. I love your honesty Maggie. War is always a sport for the rich - paid for by the young. Honour and sacrifice are fantasies we never seem to wake from.

Love xx.

Maggie Holman (Tuesday, 23 August 2022 20:21)

Alan - thank you so much for your comment. I really appreciate it.