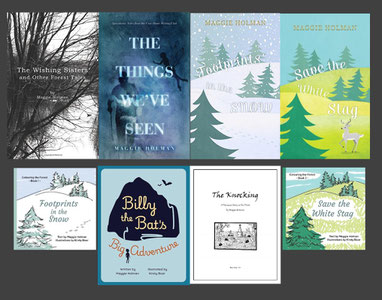

List of Read-for-Free texts: (Please scroll down to find something you'd like to read)

From Hexham to Barry - One Moment in Grandad's War (opening section)

Billy the Bat's Big Adventure (extract)

Troll Pudding (extract)

The Great Pumpkin Chase (extract)

Robot Rabbit & the Easter Egg Trick (extract)

Cliff Walk (ghost story)

Chocolate Power! Fight for Your Right to Eat Easter Eggs! (Scenes 1, 2 & 3)

Save the White Stag (Chapters 1-3)

The Things We've Seen: Speculative Tales from the Care Home Writing Club (short extracts from the 'grand reveal' short story element)

Footprints in the Snow (extract)

The Knocking (extract)

The Wishing Sisters (complete story)

A High Windy Place (complete story)

*

Opening: 'From Hexham to Barry - One Moment in Grandad's War'

1

26th June 1918

The bar was quiet. Apart from Jack, there was only a lone drinker in his work overalls, chatting to the landlord at the counter, and a young couple who sat in a far corner, holding hands and whispering. The bar was near the edge of Barry, and this was exactly why Jack was here. The bars in the town centre would be busier, full of soldiers enjoying an evening drink, and what was more, they might be soldiers who knew him.

Jack was busy writing a letter. He stopped occasionally to sip his pint of pale ale - he needed some Dutch courage to put his pen to this particular paper - and now and then he stopped and looked around, as if checking he was quite safe and hidden, as if he were expecting someone to walk into the bar and stop him.

The summer sunset streamed through the stained glass windows and the bar took on a strange luminous appearance, a glow which broke the dull browns of its day-time atmosphere. Jack checked the clock on the wall behind the counter; almost nine-twenty, time for him to leave. He finished his letter, read it through and put it in an envelope, then he sealed it up and pulled a single stamp from his wallet; first class, because it was important, and goodness knows how long it would still take in the disruption of wartime. He quickly knocked back what was left of his pint, picked up his kit bag, which had a rolled-up blanket tied to the top, and put his empty glass on the counter. He nodded a goodbye to the landlord, who was busy drying glasses. He waved back to Jack as he left but didn’t take a lot of notice of him.

Outside, it was quiet. Nobody was coming and going from the terraced houses that lined each side of the narrow back street. Here and there, warm lights shone inside the closed curtains, but many of the front doors were still wide open and a few neighbours stood chatting in the evening sun. Nobody took any notice of Jack as he turned left and walked to the street corner, where he already knew there was a post box, waiting, black mouth agape as if in anticipation of his letter. When he got there, he took the letter from his pocket. He stared at it for a moment, at the familiar address, imagined the reaction when its contents were read out loud in a quiet, cosy kitchen miles away, and then he brushed these thoughts firmly aside and popped his letter into the post box before he changed his mind.

With that job done, Jack threw his kit bag over his shoulder, turned the corner and began to walk. As he headed out of town, the terraced streets were left behind, replaced here and there by more individual houses which were surrounded by pretty gardens and vegetable patches. Walking on, he passed the entrance to a small farm and then he was out in open countryside. The sun was almost set, a beautiful sunset, Jack thought, a fiery ball of deep orange light which spread a layer of dramatic light along the horizon as far as he could see. Soon it would be completely dark, and Jack pressed on quickly. Eventually, he stopped at a stile in a fence on the roadside. Beyond it there was a wide field which stretched up a gentle slope. At the summit, a copse of trees stood sentry over the view, silhouetted dramatically by the setting sun. Jack threw his kit bag over the fence, put one foot on the stile, heaved himself over and jumped onto the grass. When he reached the trees at the top, he looked down at the wider forest area that stretched away down the other side of the hill. Up close, the trees were huge. Ancient and gnarled, they stood tall in a carpet of ferns and brambles, and the undergrowth was interspersed here and there with footpaths that had clearly been well-trodden over the years.

Jack set off down one of these paths, walking confidently with a purposeful stride. At the bottom, the path led into a clearing. It was open to the stars, but hidden away to everyone and everything else by the surrounding foliage. A large tree trunk lay on the edge of the clearing. Its explosion of roots was still intact at one end, evidence of its demise in some earlier storm. Jack sat down on the trunk, took out his tobacco tin and rolled a cigarette. After he lit it, he threw the match into the pile of spent matches and cigarette butts that already lay nearby on the ground.

Everything was going according to plan. Jack just had enough time to sit quietly, listening to the sounds of the forest as it settled down for the night, and smoke his one cigarette, before the sun reached the horizon. In a few minutes, it would be gone.

*

Jack opened his kit bag and fished about inside. He pulled out an empty soup tin that he’d cleaned up earlier. Searching again, he pulled out a round, fat candle which was a little smaller in diameter than the tin. He scooped up a small pile of dry earth and tipped it into the tin, then he put the candle on top of it, so that it stuck out above the lip. When Jack struck a match and lit the candle, its flickering flame created a comforting barrier around him. Beyond was the darkness of the clearing and the shadowy shapes of the sentinel trees.

Next Jack undid the rope from around his blanket and rolled it out. He spread it out in front of the fallen tree trunk, curled up on it and took out his tobacco tin. As he proceeded to smoke his second roll-up, watching the flickering candle-light, he suddenly heard a single cracking noise and sat up quickly. He sat up when he heard some rustling sounds, accompanied by further cracking, but he couldn’t quite work out where they were coming from. Before he had time to decide what to do, a dark shadow of a figure stepped into the clearing and took a couple of steps towards him.

In the flickering candlelight and with some help from the rising moon, Jack saw that it was another soldier, dressed in the same standard issue khaki of a British Tommy. He was slightly-built, quite smart, with slicked black hair, and looked younger than Jack, which was saying something, since Jack had not long just turned twenty. The soldier put his hands in his pockets and stood quietly, staring at Jack. Jack stared back.

“Hello,” said the soldier, eventually.

“Hello,” Jack replied cautiously.

“What’re you doing out here? Are you hiding?”

“Maybe,” said Jack. “What about you? What’re you doing here?”

The soldier didn’t answer Jack’s question. Instead, he said “I saw you walk up, from over there in the field.”

Jack stubbed out his roll-up, stood up and began to roll up his blanket.

“But…I don’t want to get in your way,” the soldier began, stepping forwards. “You don’t have to go. I won’t tell.”

Jack stopped and looked at him.

“Tell who? And tell them what?”

“That I saw you.”

There was a pause. Neither of the young men moved.

“Listen. Where are you from?” said the soldier.

“Barry,” said Jack. “Just back there.”

“How’d you get here?”

“Walked. I thought I was far enough away to be on my own, deep in these trees. I’ve hardly been here before you appeared.”

“But it doesn’t matter. I’ll be off in a minute. I just wanted to say hello.”

He stepped forward a little more.

“By the way, I’m Tom,” he said, stretching out his hand. Jack relaxed a little.

“Jack.”

They shook hands, even though the formality seemed out of place.

“Anyway,” said Tom. “You don’t have to leave. I’m off now.”

He took a few steps backwards, all the time watching Jack, heading for the tree line.

“Wait!” Jack called out. “Can I trust you?”

But Tom didn’t reply. He’d already disappeared into the shadows.

*

Once he was sure that Tom was gone, Jack immediately fastened up the blanket with its rope, then he blew out the candle. He waited for his eyes to become accustomed to the darkness and then he packed the candle and the tin into his kit bag. He tied the blanket to his kit bag again and threw it over his shoulder. He set off, out of the clearing, walking as quickly as he could in the darkness, in the opposite direction to the one Tom had taken. Now and then he looked over his shoulder, watching for the young soldier, but in the darkness it was impossible to tell whether or not he was being followed.

As Jack walked deeper into the trees, his way became more difficult. Now and then he tripped and almost fell over unseen tree roots and loose stones, or his clothing snagged on wild brambles and the lowest-lying branches of trees, but eventually he came to a spot which, in the sliver of moonlight, looked like a place where he could settle for the night. For the second time that evening, he unfastened his blanket. This time he threw it across the thickset undergrowth of ferns and lay down on it. He curled up, as comfortable as he could expect, and, exhausted now from all the activity, he fell fast asleep.

*

At some point during the night, Jack woke suddenly, because someone was shaking him violently by the shoulders and whispering his name over and over. When he opened his eyes, he saw Tom up close, looking right into his face. Jack was momentarily confused and he thought he was being attacked. He grabbed onto Tom’s arm and made to defend himself, but Tom let him go and sat back on the damp bracken. Once Tom saw that he’d successfully woken Jack up, he sat quietly and left him alone.

“What?” said Jack.

“You were shouting in your sleep,” said Tom.

“What was I shouting about?”

“Shells. You were scared.”

“I keep doing this. The other blokes in my block kept complaining and waking me up. It got so I was getting scared to go to sleep.”

“That’s a bit mean of them,” said Tom, “but anyway, you can’t make all that racket out here. Somebody might hear you. There are probably gamekeepers and such about.”

Jack sat up and stretched.

“You are hiding, aren’t you?” said Tom.

“Yes. Are you?”

“I was, but not any more.”

“That’s a strange answer. What d’you mean?”

Tom looked around.

“I heard you call out earlier, when you asked if you could trust me.”

“And can I?”

“Yes,” said Tom. “You can. Why don’t you go back to sleep? I’ll sit here and watch, and I’ll wake you if you start to shout again.”

*

Billy the Bat's Big Adventure

Billy was a bat who wasn't very strong.

He was just a little baby and his toes, they weren't too long.

He flew with his Mum to the top of the cave,

To stay there for the winter, their energy to save,

But the neighbour-bats, they wriggled as they settled down to sleep,

And he dropped to the floor in a little batty heap.

As he was lying there in a bit of a daze,

A boy came into the cave to find a fun place to play.

His name was Dave. He was a boy with a curious mind.

He liked to look for new things, and here's an interesting find!

Before Billy had time to squeak "No! Please! Stop it!"

He picked poor Billy up and he put him in his pocket.

*

Troll Pudding

Tilly’s mother kept telling her not to play in the forest.

“There are trolls in there, Tilly. They live under the ground. They like to eat little girls like you in one big gulp!”

Of course, Tilly didn’t believe her mother. Every day after school she sneaked off to climb trees and play stepping stones across the stream.

One afternoon Tilly was sitting under a big oak tree, singing to herself and making a daisy chain. Suddenly she heard heavy footsteps behind her. She peeped round the tree and was amazed by what she saw. A huge troll stomped by. He was the ugliest thing! He was completely bald and his face was covered in warts. He was as round as he was tall, and his big fat stomach stretched out in front of him. He was covered in hair and dressed in rags. Tilly watched, fascinated, as he walked over to some tall ferns, poked around in them for a moment and then disappeared!

Tilly crept over to the ferns and discovered a large hole, a tunnel that disappeared downwards. She couldn’t see the bottom at all. She was so excited to discover that the trolls were real that she forgot her mother’s warning and jumped down the hole after the troll. She slipped and bumped her way down, past tree roots and slimy worms, until she landed at the bottom with a bump.

She stood up and looked around. There was a tunnel ahead of her, also dark and muddy, and at the end was a dim flickering light. She could hear the sound of strange growling voices, and she decided to creep along to investigate.

The tunnel opened up into a huge room. It was full of trolls, all singing and dancing round a fire in the middle! There were big trolls and small trolls, boy trolls and girl trolls, old trolls and young trolls, fat trolls and thin trolls. Some had huge eyes and some had little piggy ones. Some wore rags and others wore nothing at all! One thing was certain. They all had big mouths full of sharp gnashing teeth, perfect for eating little girls, just like her mother said. Tilly looked at those sharp scary teeth and she stepped slowly backwards. She wanted to climb back up the tunnel before she was discovered.

Too late! Tilly felt two huge hands grab her shoulders. Heavy troll breath, nasty and smelly, whistled in her ear. She was frozen to the spot, until the troll who’d found her suddenly picked her up, put her under his arm and stomped towards the fire.

He dropped her on the ground. The other trolls stopped their singing and dancing. They gathered around Tilly and she stared at their ugly faces, their big hands and their sharp teeth, which were even sharper now she was up close.

“A little girl! Let’s eat her right now!” shouted one troll.

“We ate our dinner. She can be our troll pudding!” shouted another.

The trolls stepped forward, their grabbing hands outstretched, and Tilly had to think quickly.

“Wait, wait,” she said, scrambling to her feet. “Actually, I’m here to give you a message about troll pudding.”

“You are?”

“Yes,” Tilly continued. “I went to dinner with the trolls who live over the hill, and they are eating a new kind of troll pudding. They wanted me to tell you about it.”

The trolls looked at each other.

“There are other trolls?” they whispered.

“Yes, but they’re very shy, so nobody ever sees them. I said I would bring their troll pudding recipe, because they were too shy to come and tell you themselves.”

“So, how d’you make this pudding?” said a fat troll who looked like he enjoyed his food.

“Er - you need grapes,” said Tilly.

“Grapes?”

The trolls looked at each other, confused. They had probably never eaten grapes before in their lives!

“Yes, grapes, and er - yogurt, and maybe a bit of honey.”

“Oh, no, no, no, no, no, little girl,” one troll stepped forward. “You’re trying to trick us. We eat eyeballs, not grapes.”

“Yeah – and bits of puke.”

“And slime.”

“And worms.”

“And little girls!”

Tilly’s knees started to shake when she heard this, and she tried to

sound confident.

“But grapes are sort of like eyeballs, and yogurt’s a bit like slime,

and er - you could add some chopped up peaches. They would look like puke.”

“Peaches!” shouted a troll. “Whoever heard of a troll eating peaches?”

*

The Great Pumpkin Chase

Every year Tom’s Grandpa grew six pumpkins. One was for Tom and the others were for Tom’s friends, and he always made sure they were ready just in time for their Halloween trick or treat. The boys always looked forward to hollowing out the inside out of each pumpkin and making scary faces on the empty shell for their ‘Trick or Treat’ activities, while Grandpa used the pulp to make lots of pumpkin soup.

This year the pumpkins were almost ready. Tom and Grandpa walked down the garden and inspected each one carefully. Their bright orange colour was just right, their leaves were strong and healthy and they sat up straight in the soil. Grandpa tapped one of the pumpkins with his stick.

“They’ll be ready tomorrow, Tom. Come over after school and we’ll pull them up.”

“Cool,” said Tom, who couldn’t wait to make this year’s Halloween pumpkin face. “I’ll tell everyone.”

“And you mustn’t forget to come,” said Grandpa, “I’ve told you before, if the pumpkins get too ripe and we haven’t pulled them up, they might grow arms and legs and run away.”

Tom laughed.

“No, they won’t. You’re teasing me,” he said. “Pumpkins don’t grow arms and legs!”

“Aah, don’t you be so sure, young fella,” laughed Grandpa. “You just didn’t ever see them because we always remember to pick them on time!”

Tom was so excited about the pumpkins that he could hardly contain himself. At school the next day, his five friends – Stevie, Joe, Dean, Harry and Jake – were just as excited.

“Mum's going to pick us up after school and we'll go straight to my Grandpa's house. We'll make a start on our scary faces.”

However, when Mum waited at the school gates she was looking a little worried.

“What's the matter, Mum?” Tom called when he ran across to her.

“Your Grandpa's not feeling very well, Tom. I'm going to take you straight home. You can stay with Dad while I go back over there to look after him.”

“Is he going to be alright?”

“Yes. He just has a bit of a cold, but he can't be bothered to get out of

bed. I'll take him some nice soup.”

The mention of soup reminded Tom of what an important day it was.

“But what about the pumpkins?” he shouted out. “Yesterday Grandpa said that they would be ready to pick today. He told me not to forget to come, because if we don't pick them and they get too ripe, they’ll grow arms and legs and run away!”

“Don't be silly, Tom. That's just another of your Grandpa's stories. He used to tell me that all the time when I was a little girl.”

“And did you ever see them grow arms and legs?”

“Of course not!”

“But maybe that's because you picked them at the right time.”

“Listen,” his Mum said firmly. “You're going straight home, so no more complaining. We'll pop over and get the pumpkins as soon as your Grandpa's feeling better.”

Tom had to wait three whole days before he was even allowed to go and say hello. He rushed into Grandpa's house.

“Hi, Grandpa. Are you feeling better?”

His Grandpa laughed.

“Much better. Thank you for asking, Tom.”

“And the pumpkins?”

“I'm afraid I didn't even look at them these last three days. We'd better go and check on them now.”

What a sight was waiting for them in the garden!

“Oh, no,” said Grandpa.

Grandpa, Tom and Mum stood in a line, looking at an empty vegetable patch. There were six big holes where the pumpkins had been. A mess of roots stuck out of the holes and a trail of broken leaves and stalks led to the garden fence.

“They've been stolen!” exclaimed Mum. “Who would want to steal your pumpkins?”

“More like they grew arms and legs and ran away, just like Grandpa said,” shouted Tom, “because look! Over there! There's one hiding up in that tree.”

To everyone's amazement, a large pumpkin had indeed climbed up into a nearby tree and was sitting on a branch, swinging its legs.

*

Extract: Robot Rabbit & the Easter Egg Trick:

Setting: a public park. Three chairs are placed in the centre to represent a park bench. A painted banner hangs across the back which says, ‘GRAND EASTER EGG HUNT’. The scene is empty.

JIMMY comes on from stage left, pulling a cardboard creation which resembles both a rabbit and a robot. He lifts it up and sits it on the park bench.

SUSIE and JACK enter from stage right.

SUSIE: Hey, Jimmy. You finished the robot rabbit. It looks pretty cool!

JIMMY: And it has a box behind the mouth to catch all the Easter eggs. See?

He turns the rabbit around to show SUSIE and JACK, then puts it back in place.

JACK: Great. So, what are we going to do with it now?

JIMMY: I told you already. We’ll trick the other kids into giving us their Easter eggs. It’ll be easier than running all over the park looking for eggs ourselves.

SUSIE: Are you sure it will work?

JIMMY: Yes! Now listen up. One of us has to do the robot voice. Let’s all try and see who does it best. Jack, you go first.

JACK: What do I have to say?

JIMMY: Whatever you like. It’s just a practice. Why don’t you say “Hey there. Why don’t you share your Easter eggs with me? I’m really hungry!”

JACK: (putting on a robot voice) Hey there. Why don’t you share your Easter eggs with me? I’m really hungry!

They all laugh.

JIMMY: Not bad. Now you, Susie.

SUSIE: (putting on a robot voice) Hey there. Why don’t you share your Easter eggs with me? I’m really hungry!

They all laugh again.

SUSIE: Now you, Jimmy.

JIMMY: (putting on a robot voice) Hey there. Why don’t you share your Easter eggs with me? I’m really hungry!

They laugh even more.

JACK: I think you’re the best robot, Jimmy.

SUSIE: Me too. You can do all the talking.

JIMMY: Alright. Now listen, the Easter egg hunt starts in a few minutes. Let’s hide over there in the bushes and wait for our first victim!

JIMMY, SUSIE and JACK hide in the bushes. GIRL 1 skips onto the stage from stage left, carrying a bag of eggs. She stops and stares at the robot rabbit.

JIMMY: (in his robot voice) Hey there. Why don’t you share your Easter eggs with me? I’m really hungry!

GIRL 1: I don’t want to.

JIMMY: Please!

GIRL 1: No!

She skips off stage right. JIMMY, SUSIE and JACK stand up from behind the bushes.

JACK: Well, that didn’t work.

JIMMY: Yeah, but that’s our first try. It was just a practice. Let’s hide again.

They get behind the bushes just as BOY 1 walks onstage from stage right, busy counting the eggs in his bag.

JIMMY: (in his robot voice) Hello there! How many Easter eggs have you got?

BOY 1 looks up to see who spoke and sees the robot rabbit.

BOY 1: Twelve.

JIMMY: (in his robot voice) That’s a lot. Can I have some of them? I’m really hungry!

BOY 1 thinks for a moment.

BOY 1: Alright. You can have one.

*

Cliff Walk

It was the blackest of nights for two men to be making such an ominous journey, but go they must, and so William Creed, wrapped well against the cold in a heavy overcoat, followed his gamekeeper, James, along the edge of the snaking cliffs. William liked James. He thought he was gentle, clever, had potential despite his lowly station. He valued James’s opinion and honesty, and this was why he’d agreed to follow him on this late-night journey. Now here they were, picking their way along the uneven, stony path, their progress lit by the oil lamp in the leading man’s hand. William was occupied by the sound of the waves crashing onto the treacherous rocks, and so when James suddenly stopped, he bumped into him and almost tumbled them both over the edge.

“This is the spot, Mr Creed,” James whispered. “We should wait over there, away from the edge, and extinguish the light. That’s what I did last time I was here.”

“Alright,” William replied.

They took up position a little way back from the cliff edge and James turned the lamp down until the flame went out. The wind whistled past them, tossing the salt spray and tumbling the clouds, preventing the full moon from taking part in the scene. Before them, unseen, was the jagged cliff face, full of jutting rocks and small tree branches. Everything smelt of the sinister sea.

“You’re quite sure of what you saw,” whispered William, after they had been standing

there for a while.

“Quite sure, Sir.”

“And you say you’ve looked upon this person several times.”

“Yes.”

Just then, the sound of falling rocks made them both jump.

“Did you hear that?” William whispered.

“I did, Sir. Please, keep very still. We must remain hidden and secret.”

William froze, tense with expectancy. Now and then, next to the whistling wind and

the crashing waves, he heard a scraping and a pulling, a snapping of branches and a tumbling of more rocks. So - what James had reported to him that morning in his study was true; someone, somehow, was making their way up the cliff towards them.

Suddenly, the full moon broke through the clouds and a slight movement at the cliff edge caught William’s attention. He looked harder in the darkness and saw a hand, a tiny white hand, reaching upwards, scrabbling, searching, until finally it caught hold of an exposed tree root. A second hand appeared and then a shadowy figure used the root, hand over hand, to pull itself up over the cliff edge. The figure crawled a little way on its hands and knees and then stood up.

William had hoped that James was wrong, that the moonlight had tricked him, but now the same moonlight revealed the truth. His dead daughter had just climbed up the cliff. He stared at her blue-tinged face, at her wet hair, thrown loose and plastered to her head, at her frilled dress, dripping with water, at her salt-soaked boots, tattered and torn. William bit onto his clenched fist to keep from crying out as she turned and began to walk along the path. When she was out of sight, he fell to his knees, gasping for breath.

“Emily,” he cried out between breaths, “My dearest Emily.”

At such a moment, James felt he could forget his expected protocol. He bent down, put

a supporting hand on his master’s shoulder and paused a moment before helping him to his

feet.

“Thank you, James,” said William. “Where is she?”

“She always goes to the house, Sir.”

“Then we must go after her.”

The two men hurried back along the path towards Seaview, the home William had built with love on this high, exposed cliff and now wished he hadn’t. As they approached, the house was fast asleep, its windows dark, its chimneys cold.

“She always goes to the sitting room window, in the rear garden,” said James. “We should keep close to the wall.”

When they entered the garden, William followed James into the shrubs and trees. They

crept along the boundary wall until they could see the house through the foliage. At the centre was an ornate door, with three high sash windows on either side and a similar display of windows above. The familiar view of the house was now disturbed by the shadowy outline of little Emily, standing by the sitting room window. In their hiding place, William and James were behind her and could clearly see her, on tip-toes, leaning on the window sill and peering inside.

“Oh, what should I do, James?”

“There is nothing you can do, Mr Creed. Your daughter lives under the sea now, breathing in the salt water. ‘Tis a great sadness, and so I wanted to show you that I’d seen her, so that you know she finds her way back to look on her old home.”

“I’m glad you did, but oh, at the same time, I cannot bear it,” said William, through whispered sobs, “The sea took her away and she wants to come home.”

“But watch out, Sir. Look - a light.”

A dim light had appeared in an upstairs window. The two men watched as it flickered its way through the house until it came to a halt inside the sitting room window, turning Emily from shadow to silhouette. While the little girl stared in, a woman in a white nightgown, her hair hanging in a single plait over her shoulder, oil lamp in hand, stared back.

“Oh God, it’s my wife,” said William. “She mustn’t see Emily. She’s already so frail.

The shock will kill her. Can she see her, James?”

“I don’t know, Sir.”

William looked at the scene, at his daughter staring up at her mother.

“Mama!” said a child’s voice.

“She spoke!” William cried out, and he fell against the wall, helpless. “Oh, dear Lord,

what dilemma is this? Do not see her, Ann! Do not look on the child you miss so much, no

matter how much you would wish to.”

“It’s me, Mama,” said the little girl, as she reached a hand towards her mother and pressed it against the window, but Mrs Creed was oblivious to her daughter. She stared straight past her, across the lawn, searching. William’s heart broke in two when his daughter uttered a single sob, and then turned and ran across the lawn.

“Emily!” William called after her, his voice torn apart by anguish. James stood by his

side, silent. Next they heard the door open and Mrs Creed appeared. She stood on the edge of the lawn, holding her lamp high to see better.

“William? Are you out here?” she called in a nervous voice.

“Sir, you should go to your wife,” James whispered.

William started suddenly, as if he’d forgotten James was there.

“Yes, of course. Thank you, James, and please, there must be no mention of this matter to anyone, not to my wife or to the staff. We will speak further. Goodnight.”

“Goodnight, Sir.”

William brushed down his clothes and stepped onto the lawn.

“Here I am, my dear,” he called out, as Ann turned to locate him in the dark. “I just went for a late-night stroll. I couldn’t sleep.”

He took the lamp from his wife’s hand and they walked back into the house. When they returned to bed, William lay awake, listening to Ann’s shallow breathing. Would sleep ever come to him, now that he held such a terrible secret close to his heart? And, in the gamekeeper’s cottage, James also lay awake, wondering the exact same thing.

*

Chocolate Power!

Scene 1

In the classroom at the end of the school day

The children sit at their desks. MISS BLAKE stands in front of them all.

MISS BLAKE: Now then, children. It’s almost time to go home. I have one last

announcement to make. I’ve sent an email to all your parents to tell

them you won’t be joining the Easter Egg Hunt on Friday.

The children react with shouts, groans and gasps of surprise.

JACK: But Miss Blake, we always have an Easter Egg Hunt on the day before the

Easter holiday. We’ve had one every year since we started school!

SALLY: And it’s only two days away. We’ve been making our Easter headbands

and hats.

MARIA: We love looking for eggs in the school gardens.

SAM: Are the other classes joining in the Easter Egg Hunt?

MISS BLAKE: They are, but I’ve decided the egg hunt isn’t necessary and I’m in

charge of this class. You’ll all be getting lots of Easter eggs from your

parents and grandparents, and there’s a huge egg hunt in the town

park. Too much chocolate is just not good for you. Missing the school

egg hunt won’t hurt. Now, off you all go and I’ll see you tomorrow.

Don’t forget to do your homework!

MISS BLAKE leads the children offstage, out of the class, but JACK, SALLY and SAM stay behind.

SALLY: We have to do something. We can’t be the only class that doesn’t have an

Easter Egg Hunt!

JACK: All the other kids will laugh at us. We’ll be sitting in here doing our work,

while they run around outside and get all the goodies!

SAM: I’ve got an idea, but we have to work fast and get the whole class to help.

Come closer while I tell you, in case Miss Blake comes back.

The three children gather together and begin to whisper.

SALLY: Great idea, Sam! Come on, let’s go home and get started.

*

Scene 2

In the classroom. Next day.

The children sit at their desks, listening to MISS BLAKE, who stands at the front again.

MISS BLAKE: Now, it’s time for our art lesson. Last week we talked about how to

use shapes in art. Do you remember? Who can give me an example

of a shape?

A number of children put their hands up.

MISS BLAKE: Yes, Samantha?

SAMANTHA: A square.

MISS BLAKE: Very good, Samantha. Who can tell me another one?

MICHAEL, DEAN and MARIA raise their hands and MISS BLAKE points to them in turn.

MICHAEL: A circle.

DEAN: A triangle.

MARIA: A oval.

MISS BLAKE: It’s an oval, dear. Remember your vowels! But yes, they’re all good

examples of shapes we’ve been learning. Now, you all have paper

and pencils on your desks. I want you to make a nice picture using

any of the shapes we’ve talked about. It’s up to you how you use

them, and you can colour them if you want to. While you’re busy, I’m

going to mark your homework.

The children begin to draw. They talk quietly and look at each other’s work. MISS BLAKE sits at her desk and starts to look through a pile of papers.

An EXTRA walks across the stage with a sign that says ‘Forty-five minutes later’.

MISS BLAKE: Right, then. Let’s have a look at your work. Who’d like to come out

to the front and show their work to the class?

SALLY: Me, Miss Blake!

MISS BLAKE: Alright, Sally. Come and stand here by my desk and hold up your

drawing.

SALLY holds up her work. It’s a picture of lots of Easter eggs, coloured brightly.

MISS BLAKE: How interesting, Sally. You’ve used only the oval shape and you’ve

drawn lots of Easter eggs.

SALLY: I have, because I love Easter eggs so much!

MISS BLAKE: Well, thank you, Sally. Go and sit down. Who else would like to come

out and show their work?

Lots of children put up their hands. MISS BLAKE points to one of the boys.

MISS BLAKE: You can, Joe. Out you come.

JOE walks to the front and holds up his picture.

MISS BLAKE: Well, well, Joe. More Easter eggs.

JOE: Yes, Miss Blake, because I love Easter eggs so much!

The children start to giggle. MISS BLAKE looks at the class.

MISS BLAKE: Thank you, Joe. Go and sit down. Did anyone draw something

different?

The children giggle again.

MISS BLAKE: Everyone – hold up your pictures so I can see them.

The children hold up their papers. They all have drawings of Easter eggs. MISS BLAKE inspects them all.

MISS BLAKE: Well, I find it very strange that you all decided to draw the same

thing. You must be obsessed with Easter eggs! I think you all need

some fresh air. Good job it’s time for play. Off you go outside.

*

Scene 3

In the playground

The children all sit together on the ground. SALLY, JACK and SAM stand at the front of the group.

SAM: Well done, everybody. We all stuck together in the art lesson. We just need

to keep it up when we go back inside.

JACK: And Miss Blake will get the message by the end of the day.

SALLY: Just in time for the Easter Egg Hunt tomorrow!

*

Save the White Stag

Chapter 1

Adventures don’t usually start on the school bus, and this one is no exception. Today had been just like any other school day; a bit of fun here, a bit boring there. Now Caro was busy chatting to her friends until the bus came to her stop. Caro was the only person who got off here and she stepped into the warm spring sunshine. She waved goodbye to her friends as the bus pulled away and set off down one of the tracks into the trees.

Caro loved the walk along this forest track. It led directly from the bus stop to the traveller camp where she lived with her family. There were lots of tracks just like this one, criss-crossing the forest, well-trodden by hikers, joggers, dog walkers and cyclists, but on days like this, when there wasn’t a soul in sight and Caro was alone, she felt as if the forest belonged only to her.

Soon the track led Caro deeper into the trees, away from the sound of the traffic on the busy main road. As she strolled along, she took in the undisturbed forest around her. Now and then there was a crack as a twig snapped and fell to the ground. Up above, the tallest branches of the trees creaked and swayed in the breeze. The birds squabbled and squawked, and a squirrel suddenly ran across Caro’s path and disappeared up a nearby tree, making her laugh.

The afternoon was peaceful and quiet, and Caro felt comfortable in the arms of her forest, until she glanced through the trees to her right and suddenly stopped in her tracks. A flash of something had caught her eye and then it was gone, but immediately there was a sense that something about the forest had changed. Caro knew how to read the signs, and her forest suddenly felt different.

She peered into the trees, squinting to get a better look through the sunlight streaks which dappled the branches and made patterns across the forest floor. She stood still for a moment, very still, listening carefully, and then she stepped off the track. She crept through the trees, between the huge trunks of the great elder statesmen and the wisps of younger

saplings, watching out for twisted tree roots or holes in the ground which could be hidden by bracken and pine needles. The air smelt damp and musty, but the leaves beneath her feet were crisp and dry. She placed her feet cautiously and tried hard not to make crunching noises as she pushed forwards.

Soon the trees began to stand closer together. Their branches reached out and clasped hands with those of their neighbours, pushing away the sunlight and leading Caro into a world of shadows. Eventually she arrived at the top of a gentle bank which sloped down to a small stream. She made her way down, sliding on damp moss, and stopped by the water to look around. Caro had a strong sense that something had just been here and she was trying to work out what it was, when a particular fir tree further downstream caught her attention. She jumped the stream and headed towards it.

The tree was large, with lower branches which spread out wide and hung low, and up close, Caro could clearly see a hint of shimmering shining light along one of these branches. The edge of the branch was coated in a mysterious silvery layer, which was there and not there at the same time.

Caro bent down and inspected the ground below the shining branch. The earth was bone dry and there was no suggestion of an imprint to help her work out who or what had just been beside the tree. She stood back up and moved around to inspect the shining branch from different angles. It seemed to be brighter or darker depending on where she stood; something to do with the sunlight, perhaps, although Caro wasn’t convinced. She wondered what it would feel like if she touched it and then she decided not to. Instead, she pulled her mobile phone from her pocket and took some photos. She stepped back to survey the branch once more, then she turned around and went back up the slope, the way she’d come. When she emerged back onto the track, she gathered some small stones together, heaped them up into a pile to make a marker at the base of the closest tree and then headed for home.

Chapter 2

“When’s Caro coming? I want her to draw me a picture!” said Molly, for the hundredth time.

Molly was following her Mum around like a puppy. Now they were standing behind their caravan home, next to the washing line. Annie put down her clothes basket and began to unpeg the dry washing. She looked down at her daughter.

“She’ll be here soon, Moll. School’s just finished.”

“But how long is soon?”

“Not long. Why don’t you go and play with Finn?”

“He went for a walk with Daddy. Anyway, I don’t want to play with Finn. I want Caro to draw me a picture. She always makes…oh there she is! CARO!!!”

Molly immediately forgot about her Mum and disappeared round the side of the caravan. She ran across the clearing in the centre of the camp, wrapped herself round Caro’s legs and held on tight, giggling.

“Hey, now I can’t walk, silly!”

Caro prised Molly off, lifted her up and carried her towards the caravan.

“So, how was your day, Moll?”

“I dunno. I forgot. Will you draw me a picture?”

“Of course.”

The two sisters went inside the caravan, where Caro changed out of her school uniform and into some jeans and a T-shirt. She opened her bedroom window, peeped out and saw Annie getting the last of the washing.

“Hi, Mum.”

“Oh, hi, Caro.”

“Do you need a hand?”

“No thanks. Almost done.”

Caro went through to the dining area, where Molly was waiting at the table, her little hands clutching a sketchbook and some coloured pencils.

“So, what should I draw for you today?”

“A shark,” said Molly.

“Why a shark? Yesterday I drew a playground with you and me in it.”

“But today we had a story about a shark that went to school and was scaring all his friends.”

“Alright. Shark it is!”

Caro drew a huge shark. She made sure it had a smile and looked friendly. Molly was happy with the result and she settled down to colour it in. While her little sister was occupied, Caro took out her phone and scrolled through the photos she’d taken on the way home. The single branch of the tree was definitely shining with some sort of mysterious, other-worldly sheen. Suddenly Annie opened the caravan door and Caro put her phone away again.

“Here, Mum. I’ll put the washing away.”

“Thanks, Caro. Oh, I like your shark, Moll, but can you move onto the sofa or your bed to colour it in? I want to set the table.”

Later that evening, after the family had eaten dinner and Molly and Finn were tucked up in bed, Annie sat outside on one of the plastic garden chairs, enjoying a bit of peace and quiet in the late sunshine. Chris was planning to go and see his friend Pete for a game of chess.

“Dad,” said Caro, as she watched him pulling on his jacket, “Can I show you something?”

“Sure. What is it?”

Caro showed her Dad the photos of the tree. He studied them.

“Nice photos, Caro. Why did you take them? Are they for a school project or something?”

Caro looked at Chris.

“You don’t see anything strange in them?”

Chris looked again more carefully and shrugged his shoulders.

“No, just a nice old fir tree, set in its natural surroundings. Why? What am I supposed to see?”

Chris smiled and ruffled Caro’s hair.

“Are you playing some sort of trick on me?”

“No!”

“OK. Well, I’m off to Pete’s for a couple of hours.”

“Jamie’s arriving tomorrow,” said Caro, “Are we still going by after school to see him?”

“Of course. Right then, I’m off.”

Caro pulled on a hoody and followed Chris outside. The sun had just reached the tops of the surrounding trees on its journey to bed and the air had taken on a spring chill. The camp was also settling down for the evening. Several children were playing together in the central space. Around its edge, smoke wafted up from wood burners inside the caravans and vans, filling the air with a delicious woody scent. Across from Caro’s home, two men were working together to repair a bicycle. A group of people chatted on a nearby bench.

Caro sat down next to Annie. They waved to Chris when he headed off to his car and he beeped the horn as he drove off. Once he was gone, Caro showed her photos to her Mum.

“Nice tree,” was all Annie said, confirming Caro’s suspicions.

They sat together for a moment without speaking, watching the sky turn into a pink and purple twilight. When a couple of Annie’s neighbours came over, Caro stood up and offered one of them her seat.

“I’m just off for a walk,” she said.

“Alright,” Annie replied, “but make sure you’re back before it’s properly dark.”

Chapter 3

Caro set off, walking quickly, and went back along the track which led to the bus stop. She searched for the little pile of stones she’d left that afternoon, found them, stepped into the trees behind them and followed her earlier route. When she arrived at the top of the bank which led down to the stream, she stopped for a moment and looked across through the trees.

It mattered that Caro’s parents hadn’t seen the shining branch in her photos, so she’d intended to come back to check on it. Now, as Caro looked out across the little dell and the stream bubbling by at the bottom, the atmosphere of the forest felt different again. It could just be the approaching nightfall, changing the mood of the shadows in the trees, or it could just be Caro’s own feeling that she hoped something was going to happen, or it could really be a sign that something special was near, something ‘extra-natural’, as her Gran would say. What had her Gran taught her? She’d taught Caro to trust her instincts and her feelings, and right now, whatever the reason, the air definitely felt electric with expectation.

Caro was just about to set off down towards the stream, when something moved on the opposite bank and interrupted the stillness. She caught the sudden movement out of the corner of her eye. Something large had just moved between the trees and interrupted the twilight shadows. Caro waited for a moment and when she didn’t see any further movement, she began her downhill walk. She moved more cautiously, slowly, stealthily, like a stalking hunter, making sure she didn’t step on any snapping twigs. When she reached the bottom of the bank, she stopped behind a clump of fir trees.

Caro glanced up the stream to the fir tree she’d photographed that afternoon. There it was, the shining branch. Its silvery sheen was even brighter in the almost-darkness, but then as Caro’s eyes became more and more accustomed to the twilight, she began to notice the same shining sheen dotted here and there. There it was, along the low branches of some of the other trees and on the thin trunk of a nearby sapling. Further over, up on the bank, a shining streak travelled along the mossy ground. What was going on?

Excited, Caro took her phone from her pocket and prepared to take some more photos, when suddenly the trees opposite her began to rustle and shake. They moved apart, making way, and a huge stag walked out into the open. Caro stared at it, unable to believe her own eyes, as it walked down to the stream and bent its majestic head to take a drink. The stag stood out against the dull, dark foliage because it was white. It was an eerie, twilight-tinged white.

The white stag! In all her years of living in the forest and in all her woodland wanderings, Caro had never seen the white stag, and now here it was, not three metres away from her, and what was even more amazing was that the stag’s huge antlers were covered in a gentle sheen, a shining that was there and not quite there at the same time, twinkling and glinting in the dim light as the stag moved its head.

Making slow, careful movements, Caro abandoned her photo-taking plan and set up the video instead. She couldn’t miss this opportunity. She held up her phone, pressed play and silently filmed the stag as it finished its drink, turned away from her and followed the stream. It sniffed and rooted along the ground, stopping now and then when it found something to eat, and as it walked close to a nearby tree, its antlers brushed up against some of the branches, and immediately a shining silver line appeared where they’d touched.

Caro carried on filming until the stag disappeared into the darkness. She couldn’t contain her excitement. Just wait until she told everyone! Oh, just wait till Gran and Mum and Dad and Finn and Molly and Pete and Jamie and Lyn see her video! If there actually was more than one white stag in the forest, as some people said, then she’d just seen the legendary one, the white stag that was only seen when there was a reason, the white stag that had magical powers. The question was, why was it here now?

*

Extracts from 'The Things We've Seen'

'One Good Turn'

The heavy snow had begun at first light, and the heaviness had kept the day dark. There was an eerie silence that only comes with snowfall and the thick snowflakes swirled and danced, quickly forming a deep white carpet. Harry had been trying for some time to clear a path to the garage so he could retrieve the car, but he had to accept that he was losing the battle. He was too old for this kind of work and no-one was there to help. Now his wintry foe was winning, and its attack couldn’t have come at a worse time.

Harry leaned on his shovel, out of breath, and looked across the garden. The tree line boundary was a blurred image behind the snowy curtain and the road beyond was silent. Nobody was going anywhere today. Anyone with any sense was inside by the fire. Harry’s boots sank into the snow as he pushed his way back to the house, where he leaned his shovel up against the wall and climbed the steps. He felt carefully for the wooden slats of the rickety front porch; now was not the time to fall and break something. Martha needed him.

Inside, Martha listened to the sound of boots stamping on the doormat, then the front door opened and closed again quietly.

“Harry?” she called.

Harry followed the sound of Martha’s soft voice through to the living room. The fire he’d built earlier still crackled quietly in the hearth and Martha was still sitting exactly where he’d left her, on the edge of the bed by the window, dressed in her boots, coat and scarf, clutching her small overnight bag with both hands. He paused, then he went to hug her.

“I’m sorry, sweetheart,” he whispered into her ear, “I can’t get anywhere near the car.”

“It’s alright,” she replied, turning to gaze up at him.

Slowly, she put down her bag and took off her coat. Harry pulled off her boots for her and helped her to sit back on the bed. He curled up beside her and they both stared out at the weather for a moment without speaking.

“Perhaps we can get there tomorrow,” Martha said at last, “I’m sure it won’t make that much difference if I don’t get to the hospital today.”

When Harry bent to kiss the top of her head, Martha missed the momentary look of pain that crossed his expression.

“I hope not,” he whispered, and then cheered up, “Right, then. I'm going to make us both a nice cup of tea.”

Martha didn't reply. She continued to watch out of the window. On his own in the kitchen, Harry gripped the countertop and closed his eyes. It had been really important that Martha got her treatment today, and they were trapped here.

When Harry carried their mugs of tea through, he was surprised to see that Martha had pulled herself up and was peering out into the garden. She was suddenly animated.

“Harry, come here, quickly!”

Harry put the drinks down on the windowsill and sat back down next to his wife.

“What is it?”

“Look,” she whispered, “Over there.”

He stared at the invading snow. It was falling faster than ever, and the evidence of his earlier efforts to cross the garden was already buried deep.

“What am I looking for?”

“Over there,” Martha repeated, “There's something lying in the snow.”

Harry squinted and tried to look through the blizzard.

“I can’t see anything. All I can see is snowflakes.”

“I’m sure I saw a buzzard fly at some little bird, and the poor thing fell out of the sky and landed in the garden. It was a little black shape. I can hardly see it now, but I know it’s out there.”

'Look Who Came to Help When You Were On Your Own'

Fingers of lightning flashed through Emma's bedroom curtains. She lay curled up on her side, listening as the thunder claps came closer and closer, counting the seconds in between just like she did when she was as a child. She nursed a headache which seemed to pound more and more in time with the storm. Finally she could bear it no longer. She sat up, swung her legs over the side of the bed and got up in search of painkillers.

She peeped into Katie's room, and then into Jake's. They were both fast asleep, undisturbed, arms flung wide, deep in their dreams. As she turned to leave Jake's room she noticed that the window was open a little. The curtains blew gently in the breeze. For certain it was closed when she had tucked Jake into bed. She walked across to the window and pulled it shut, making a mental note to remind him not to open it again when he settled down for the night.

Back in the hallway Emma stopped by the telephone table at the top of the stairs. The message light was flashing on the answer machine cassette. She pressed the play button and listened. It was Paul.

“Hey baby. Sorry I didn't get to call before you went to sleep. I was stuck in a meeting that went on forever. See you tomorrow evening. Hug the kids for me. Love you.”

She pressed stop to end the message and continued on to the top of the stairs, where she flicked the light switch. Nothing happened. Power’s down. She stepped carefully onto the dark stairs and held onto the banister. Step by careful step, she went down the stairs, her journey lit up now and then when the lightning flashed through the windows. Just as she was almost at the bottom she missed her footing, slipped awkwardly and fell backwards. She lay there for a moment, winded, and rubbed at a strange pointed pain in her left side.

In the kitchen she found some paracetamol in a drawer and poured a glass of water. She swallowed the tablets and put the glass back on the drainer. She turned to go back to bed. Suddenly a particularly bright flash of lightning lit up the kitchen and Emma stopped in her tracks. Someone was there. Emma squinted in the dark. An old woman in a dressing gown and slippers, her hair tied up in a bun, was standing in the corner by the back door. For a moment the two women stared at each other, then Emma's breathing slowed and she regained her composure.

“Who are you? What are you doing?” Emma challenged, “And how did you get in? Did you break in?”

“This is my house. Why would I break into my own house?” The old woman stepped forwards as she spoke. “I woke up just now with a terrible headache and came down to find some paracetamol, but I'm confused. The kitchen looks just like it did years ago, before we renovated it.”

“Listen,” said Emma patiently, “this is my house, not yours. I don't know how you got in here, but you need to go home. Where do you live? Is there someone I can call?”

The old woman shuffled across to the kitchen table, sat down and stared at Emma. She stared for a long time before she spoke.

“I know you,” she said quietly.

“You do?”

“Yes. You’re Emma Phillips.”

“What? How do you know my name?”

'In My Garden'

Daisy was pretending. Every time she spoke to someone on the phone or replied to an email, she told them she was fine. She smiled gratefully to the volunteers who delivered her groceries and she waved to the neighbours from her window. She spoke to her daughter, Lisa, every evening, to touch base and to read instalments of her favourite children’s books to Lisa’s daughter, Lois. To the outside world, she was the same old Daisy, but inside, she was beginning to feel empty. With no-one to talk to for long periods at a time, Daisy began to talk either to herself, or to the things around her.

“Mad old bat!” she thought, “What would anyone say if they could hear you?”

Every morning, Daisy went out into the summer sunshine via the French windows of her South London town house. She crossed the patio, took hold of the handrail with her gnarled arthritic hands, walked gingerly down the concrete steps and set off across the lawn. The garden was kept apart from the outside world by high red-brick boundary walls, and over the forty years Daisy had lived there, she was the one who’d lovingly created this hidden gem, and so she felt it was reasonable to say hello to every blossom, every leafy shrub, every grand tall tree, because really they were like old friends.

The garden was long and narrow, just like all the others in the terraced street, and on this particular morning, Daisy decided to wander down the path which snaked through it. She walked slowly and carefully, because her age required it, until she came to the low brick wall which separated the landscaped section of the garden from the wild flower garden at the end. This unkempt meadow-like expanse was Daisy’s favourite part of the garden, and she loved to survey her mish-mash of cornflowers, kingcups, forget-me-nots, daisies and columbine, the cow parsley, poppies and foxgloves and the ivy and honeysuckle which wound their way up the walls like a theatre backdrop. Every plant was Daisy’s contribution to the welfare of bees, butterflies and other insects and, unlike the landscaped section of the garden, she’d left it alone to grow in gay abandon in whatever way it fancied.

She sat down on the wall for a moment, a little out of breath, and was surprised at just how overgrown the wild flower garden had become. Gay abandon was all very well, but creating a space which enabled the torture and strangulation of the floral world was quite another. Making her way through to the back gate would be a bit of a challenge, as tendrils, plant roots and grasses had tangled themselves around each other across the path, creating a veritable death trap for her unsteady feet.

“Well, I hadn’t noticed just how overgrown you’d become!” she said out loud.

“Then it’s about time you got down here and tidied it up a bit,” said a voice, “It’s turning into a jungle down here. It’s positively dangerous!”

Daisy lost her balance at the unexpected reply and almost fell off the wall in fright. She waited, but no further words came. The gentle breeze blew across the silent flowers. She looked around. Who just spoke to her? A neighbour, watching out of their window, to poke fun at her garden neglect? A passer-by in the back lane peeping through the gate to play a trick? Or did she imagine she just heard a voice, because she was a mad old bat after all?

“Hello? Hello?” she finally called out, tentatively.

“Hello? Hello?” mimicked a sing-song voice.

Daisy looked around quickly. She was confused. No-one was there. She was definitely alone.

“I expect you’re wondering where I am?” said the voice.

“I expect I am,” said Daisy.

“Look down here, a little to your left.”

“It looks like I really am having a conversation with a flower!” thought Daisy, “How can that be?”

She leaned forwards and to the left, as instructed, and peered into the tangle of grass, ferns and blooms. At first, she saw nothing out of the ordinary, but then, as she watched, the plant stems close to the ground began to move.

*

Footprints in the Snow (extract)

Without waiting for his older sister, Finn walked confidently into the opening. When Jamie followed Caro and Molly into the darkness, he discovered that they were actually in a tunnel. There was a glow of daylight up ahead, and Jamie guessed that just a little further on, the tunnel would open out into a cave. The cave was much higher and wider than Jamie had expected. The light was created by a hole in the roof which allowed a shaft of sunlight to penetrate the darkness. The light revealed pale stone walls, worn and gnarled with age and covered in moss. The walls were damp and the cave had the same earthy smell as the tunnel. In the centre, at the brightest part, four small rocks were placed evenly in a circle. Caro, Finn and Molly sat down on three of them in such a familiar way that Jamie knew they came here all the time.

“That one’s yours,” Finn pointed. “We pulled it over this morning, before we came to get you.”

Jamie joined the others and sat down on his appointed stone. He looked around.

“This is so cool,” he said. “I don’t think there’s anywhere like this in London, or anywhere else!”

“And when we came this morning to move your rock,” said Caro, “we left a packed lunch here as well.”

She walked over to a darker corner of the cave and came back with a rucksack. Inside were sandwiches, drinks and fruit. They ate the food hungrily, and afterwards Caro reached back inside the rucksack and pulled out a giant bar of chocolate. She broke it into squares and passed them around.

“We come here all the time, don’t we, kids?”

Finn and Molly nodded, their mouths full of chocolate.

“No-one ever comes here,” she continued, “because no-one else knows it’s here.”

“Is it safe here?” Jamie asked.

“Yes,” Caro snorted, as if the question were unnecessary. “Why wouldn’t it be?”

Jamie shrugged. He decided he wouldn’t even bother trying to explain what his life was like in London, that there were no safe secret places to play in, that his Mum would never let him play outside all day like this.

“But what about the panther? My Grancher says there’s a panther here. If there is, aren’t you worried it might get in here? You wouldn’t be safe then, and nobody could save you.”

The children were surprisingly serious now.

“All the forest animals have their own space. They understand each other, don’t they, Caro? If you don’t bother them, they won’t bother you,” said Finn quietly, sounding wise beyond his years.

“What – you mean there actually is a panther living here?”

Jamie was looking at Caro, who shrugged her

shoulders.

“I’ve never seen it myself,” she replied, speaking as quietly as Finn, “but that doesn’t mean it isn’t there.”

Suddenly Jamie felt that the atmosphere in the cave had changed, and that somehow he was delving into something private, something he wasn’t part of because he didn’t live here; the forest wasn’t part of his everyday world. Just then his daydreaming thoughts were interrupted when Molly piped up.

“Anyway, Caro can talk to animals, so if the panther came in here, she’d tell it to leave us alone and go away.”

Everybody laughed and the ice was broken. The sense of fun was back.

“What d’you mean, talk to animals?” Jamie laughed. “You mean like Dr Dolittle in the film?”

“Caro learns special things from our Gran,” Finn explained. “She can talk to animals, and she can use the secret signs in the forest. Gran shows you, doesn’t she, Caro? And one day she’s going to show me as well.”

Caro was quiet. She smiled at Finn for a moment, as if she were about to say something, but instead she jumped up from her rocky seat.

“Come on. Let’s play on the rope swing, see if Jamie can stay on longer than any of us.”

The children had to walk further into the trees to locate the swing. Caro climbed up a tall oak tree and unfastened it from where it was looped around a branch, out of sight. The long rope was threaded through a plank of wood to make a seat and then tied

underneath in a large knot.

“Dad made it. No-one knows it’s here ‘cept us,” Molly whispered as she tugged at Jamie’s sleeve. “Another secret, like our cave.”

Each of the children took a turn on the swing. They climbed up and sat on the plank while everyone else pushed, or they stood up on the plank if they were feeling more daring. Jamie and Caro helped the two younger children to hold on together, sitting side by side. Jamie couldn’t believe the fun he was having, and he felt a little jealous of his new forest friends and their huge playground. Back at home, his own terraced house was surrounded by rows and rows of other houses. The only places he had to play in were their small back garden and the local park.

When Finn and Molly started to look tired, Caro suggested they head back. Jamie had no idea what time it was, but the sun wasn’t far off the tops of the trees and he guessed it was late afternoon. He followed Caro again, back through the maze of trees, until they climbed out onto yet another cycle track. Caro lifted Finn up to give him a piggy back. Jamie did likewise and picked Molly up. In seconds she was fast asleep, snoring into his ear.

Jamie and Caro chatted quietly as they walked along. Jamie told Caro all about where he lived in London. He described his house, his school, the busy, built-up areas, the parks, the constant sirens, the noisy traffic and the planes passing overhead.

“I think I would hate to live somewhere like that,” Caro commented. “I’m just so used to all the open space out here.”

“Have you always lived out here, in your caravan in the forest?”

“No, not always, but we’ve always lived in the countryside. We live here most of the year and then in the summer holidays we go off to other traveller sites, or maybe to some festivals. Last year we went to Spain, high up in the mountains. It was beautiful.”

Jamie was about to ask something else when Caro suddenly whispered “Ssssh.” She stopped walking and looked into the trees. Jamie couldn’t see anything but trees, and he thought of the panther and felt afraid, but then Caro smiled and nodded across to her right.

“Look,” she whispered.

Jamie followed Caro’s gaze. At first he still couldn’t see anything, then suddenly a piece of the forest seemed to move and sway. A large stag, tall and majestic, wandered out of the trees and stopped in front of them on the track. At first it nosed around on the edge, unaware of the children, but then it turned and saw them in the half-light. Jamie nervously whispered “Caro?” but before he could say anything else, she raised her hand to quiet him. She put Finn carefully down on the ground and stepped slowly towards the stag. Finn also seemed nervous, and he reached up and slid his hand through the crook of Jamie’s elbow.

Together they watched as Caro reached out gently with her left hand. Jamie heard her make soft clicking noises with her tongue, and now and then she made a gentle “Sssssh” sound. Jamie thought that this was how you would approach an animal you weren’t sure of, like the big dog at the end of his street. Caro suddenly stopped the clicking and shushing noises and began to speak in an almost-whisper – strange words he’d never heard before, words that certainly weren’t English. Jamie looked down at Finn, who was grinning at him.

“Told you,” he whispered. “Watch. Caro will send the stag away so we can get past and go home.”

When Jamie looked back at Caro, he saw that the stag was walking slowly towards her. She was still holding out her left hand and the stag nuzzled gently into it, as if it were saying hello. Caro reached up with her other hand and stroked the stag’s broad nose, all the while speaking in her strange language. Finally the stag turned back towards the trees. It paused and then darted off into the undergrowth, where in seconds it was lost from view. Caro looked back over her shoulder and grinned.

“That was so cool!” Jamie said, quite amazed. “You really can do that stuff, just like Finn said!”

Caro looked pleased as she walked towards them and lifted Finn onto her back again. All the way home, Jamie threw questions at her - How did she remember that strange language? Where was it from? What was she saying? - but Caro simply smiled and refused to share her secrets. When they arrived back at Grancher Pete’s garden, he was waiting for them by the back gate.

“Caro spoke to a stag!” Jamie said excitedly.

“Did she now?”

Grancher Pete smiled and threw Caro a knowing glance.

“Thanks for bringing Jamie back, kids. Best jump in the car, though, Caro. I’ll take you round the road way. It’s too dark to be walking back with two tired little’uns.”

Caro climbed in the front of the car with Pete, while Jamie sat in the back with Molly on his lap and Finn curled up next to him. In minutes they were asleep, and as Jamie thought about the wonderful day he’d had, he gradually gave in to his own deep slumber, and dreamt he was swinging through the trees on the antlers of a giant stag.

(Extract from Chapter 5: Footprints in the Snow)

*

The Knocking

'The Knocking' is a supernatural novella based around the Great Flood of 1607, which devastated the South West of England and in which over 2000 people drowned. In this contemporary story, university student Megan spends her summer break researching the flood. She gradually realises that the lives of people living in the present and the ghosts of the past are interacting in a way she could never have imagined.

Back at the cottage, I decided on a run. I got changed and set off along the sunlit path. I concentrated on my breathing and my pace, as I ran on and on in an effort to escape my thoughts. Jack's boat had unsettled me, although I couldn't say why. I ran on a bit further than on my previous runs. The path lay closer to the edge of the river, twisting and winding alongside it like a faithful friend. Ginny was right; it was a nice route. I rounded a new bend and unexpectedly came across a wooden bench. Behind the bench, on the inland side, a wide marshy area was overgrown with reeds and bulrushes. It stretched all the way back towards the hillside. The bench was placed so that it looked towards the river, an ideal spot for passers-by to stop and take in the view. It seemed to beckon to me to sit and rest, so I did. I leaned back, stretched my arms along the warmth of the wood and surveyed the scene in front of me. The river was calm and flowed smoothly by. A few twigs and leaves and the occasional duck floated along in the swirling current. On the opposite bank, the flat fields stretched away into the distance. The trees and fences grew smaller and smaller, stretching away in pop-up layers until they disappeared over the horizon.

No-one had passed me on the path. No canoes or boats putt-putted by. I couldn’t even hear any birds singing. I was just getting my breath back and thinking about how quiet it was, when the peaceful moment was broken by the sound of giggling behind me. I turned quickly, but all I could see were the reeds, blowing from side to side in the gentle breeze. The giggling had sounded young, girlish. I was sure I heard two different voices. I bent down and tried to peer through the tangle of leaves and reed stems, fully expecting to find a couple of mischievous teenagers hiding from me, but no-one was there.

I watched the reeds a little while longer, then I turned back around. Immediately there came the sound of more laughter. This time it seemed to come from the left of me, but when I looked in that direction, more laughter came from in front of me. How could that be? The laughter continued, behind me again, then to the right, left, right. I stood up and turned in all directions, this way and that, until I felt dizzy from trying to keep up. Wherever I looked, no-one was there. I tried to step down into the reeds to explore further, but my trainers threatened to sink into the soft, waterlogged ground.

“Hello?” I called out to the invisible voices. “Who's there? Are you teasing me?”

The laughter stopped immediately. I waited, a little unnerved, but everything stayed silent. I turned around and ran quickly back to the cottage, where I found the puddle waiting for me.

*

The Wishing Sisters

This is the first story in the short story collection of the same name. You can read the whole story below. 'The Wishing Sisters' collection is available at amzn.to/2oHvNvK. There is also a reading comprehension resource for this story at bit.ly/2GkE5zu & bit.ly/2xXJ6tc.

The Wishing Sisters

November 26th 1888

At eight o’clock this morning, my husband Jacob left me. He didn’t mean to, but he went anyway. No-one could have seen it coming – a collapse in the main pit, everyone buried. It was a little boy who told us. He ran all the way across the fields until he reached our row of houses. Poor thing! We bathed his bleeding feet where they were cut and blistered, and he lay back against my neighbour Amelia’s garden wall and told us all, in short breathless sentences, the terrible news. The rescue was quick. One thing about mining accidents is there are always other miners there to help straight away. By nightfall they had everyone out – forty-two in all – and all of them dead. The worst disaster for years, it said in the local paper.

They brought Jacob home and laid him out on our kitchen table. He was a shadow of his living self. His pale face seemed wrapped in sleep, and while I sat with him that night – for I wasn’t afraid – I felt that at any moment I could reach out and shake him, and he’d wake up. But I knew there was no waking up for Jacob, never again. And all I could think about was the times I’d woken in the night and whispered ‘I love you’ into his ear as he slept, and had I done this enough times? Had he gone on his final journey, with forty-one souls in tow, knowing how much I adored him?

December 1st 1888

The mining company wasted no time. I couldn’t stay in our home now that I was alone. These cottages are for miners and their families. The letter reminded me when it arrived, the day after Jacob’s funeral, so I have done the only thing I can, with reluctance, and written to my brother Michael to ask for a room in his home.

December 3rd 1888

What a speedy reply came from Michael! Instead of writing back to me, he arrived today with his horse and cart, accompanied by his youngest daughter, Martha. Together we packed up my belongings and set off for the farm. I have not seen Michael for some years, even though we had always been close. He and his wife Sarah live a good distance away, on a farm Michael saved hard to buy before he proposed to her. The year they married, the snow fell so badly the night before that Jacob and I were trapped in our home, unable to attend. Michael understood our lack of control over such things as weather and travel, but my new sister-in-law was not so forgiving, and she never spoke to us again after we missed her special day. This was the reason for my

reluctance to write now. I lived in a happy home with Jacob, and I now travelled with trepidation

to take a place under Sarah’s roof, where in spite of Michael’s cheerfulness, I expected to find tension.

Sarah was waiting at the door as we pulled up in the farmyard. She greeted me civilly but frostily, and showed me around the house while Michael and two of his farm workers took my things to the spare room. We all sat down to dinner at the huge kitchen table that evening – Michael, Sarah, my two young nieces Martha and Elizabeth, and myself – and everyone ate in stony silence. Afterwards I went to my room, looked at my wedding photograph in a frame on the bedside table and wept into my pillow.

December 6th 1888

I have been here at the farm for three days. My two nieces are delightful. Their company cheers me up and distracts me from my thoughts. Michael is usually absent until the evening, out on the land, and I am trying my best to endear myself to Sarah with offers of help around the house and with the girls. I get the impression that I cannot win, as Sarah seems happiest when she refuses my offers, as if I am intruding into her control of the domestic domain. I think this may be used against me at some later date.

December 7th 1888

Last night I had the strangest experience. I woke with a start. The clock on the wall said three o’clock, and I listened to the darkness, wondering what had awoken me. After a few minutes I heard a sound. It was the distinct, unmistakable sound of a woman crying. Carefully I got up, put on my dressing gown and lit the oil lamp that stood next to my bed. I opened my bedroom door, hoping not to disturb anyone with its creak, and looked up and down the landing. The farmhouse is big but not sprawling, and in a few minutes I was able to explore the whole of the upstairs area. No-one else was about, investigating the sound, and I set off downstairs to search there. Again, I found nothing. The crying gradually subsided and I set off back to my room.

As I turned at the top of the stairwell, I jumped in fright, and then relaxed, when I realised it was Sarah standing in the moonlight.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I heard someone crying – a woman – and I went to investigate.”

“Impossible. There’s no other woman here. Only you and me.”

“Well, it was probably a dream,” I said as I stepped past her.

Just then, Martha opened her door, rubbing her eyes sleepily.

“There – now you’ve disturbed the children. I’ll thank you not to start making a habit of wandering about in the night.”

Sarah hushed Martha back into her room. She closed the door behind her and left me

standing in the passageway, trying to make sense of what I’d heard.

December 8th 1888

This afternoon I was sitting in my room, reading. I looked up to see Elizabeth standing in the doorway. I smiled at her.

“What is it?”

She hesitated and then walked across the room. She stood by my chair and looked around. Something seemed to be bothering her.

“Elizabeth – is something wrong?”

Finally she spoke.

“I heard the crying last night,” she said quietly.

“You did? Then I didn’t imagine it.”

“And I’ve heard it every night since you came.”

I stared at her, confused.

“Did you ever hear the crying before I came to stay?”

She nodded a ‘no’.

“It was you, Aunt Hannah,” she blurted out.

“What do you mean?”

“You were crying last night. You’ve been crying every night since you came. I can hear you in my room.”

I froze, unsure what to say.

“But it sounded like it was coming from somewhere else,” I protested. “I couldn’t find out where.”

“No,” Elizabeth said firmly. “The crying is inside you.”

She turned and walked out of the room, and I was left wondering why a small child would say such a strange thing.

December 9th 1888

In the last few days, I have taken to walking in the woods on the edge of the farmyard. The trees remind me of the area around my own home, and I believe there is nowhere on earth that gives a person the sense of peace and solitude that I get when I walk in these woods alone. At this time of year the bare, leafless trees, the still, dark surfaces of secluded ponds and the eerie mist that hangs over everything, all combine to create a picture that mirrors my sadness. I think it is helping me when I walk deep into the trees, sit by the still water and remember those memories that only belong to me and no-one else. I need to do this, because I don’t know what else to do. I feel so alone.

Imagine my surprise then, today, when I turned a corner in the path and saw someone – a